Biography

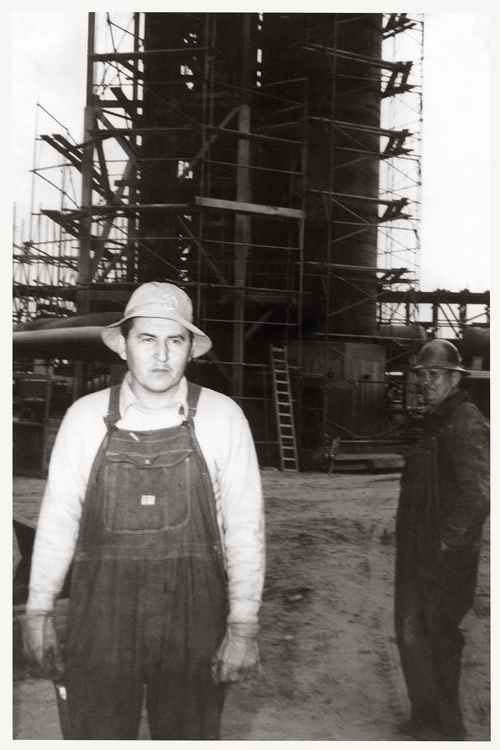

“I work with clay and pull it around and see what I can do with experimental forms. When I’m creating something, I’m there with the clay, and after a while something begins to build. One of the good things is creating something that you’ve never seen before.”

Allan Houser, who came to create many things people had never seen before, was born Allan Capron Haozous on June 30, 1914. Ha-oz-ous, in the Apache language, describes the sound, the sensation of pulling a plant from the earth and the point at which the earth gives way. His middle name, Capron, came from Captain Allyn K. Capron of the U.S. 7th Cavalry at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Capron was the first Army officer to die in the Spanish-American War of 1898.

Houser’s parents, Sam and Blossom Haozous, belonged to the Chiricahua Apache tribe — hunter-gatherers, who roamed from northern Mexico to New Mexico. Sam’s father was first cousin to the legendary Apache leader Geronimo, and a member of the Warm Springs Apaches (who had roots in Hot Springs, New Mexico, about 60 miles north of what is now Truth or Consequences). In 1886, after years of resistance and exile, Geronimo surrendered to the U.S. Army in Chihuahua, Mexico, and as punishment, he and about 1,200 of his followers were imprisoned and sent by train —most in cattle cars — to prisons in Florida, Alabama, and Oklahoma.

Sam Haozous was among the women and children jailed in St. Augustine, Florida. Blossom, whose father, George Wratten, served as a U.S. Army scout and interpreter and essentially betrayed Geronimo to the government, was born in the prison camp at the Mount Vernon Barracks, Alabama. Her mother, Annie White Gooday, and other surviving members of the tribe were sent there in 1887. Both Sam and Blossom were among the 250 Chiricahua later sent to Fort Sill, where they remained prisoners for 20 years. When they were finally granted their freedom late in 1913, Sam and Blossom were among the 14 families who chose to stay and farm close to Fort Sill. In 1914, Allan was born; the first child in his family to be born out of captivity.

An inquisitive child who loved being outdoors and drawing, Houser also went on to become a Golden Gloves boxing champion. In 1934 he saw a notice at the Indian Office in Anadarko, Oklahoma, inviting applicants to join the Painting School at the Santa Fe Indian School. This was the so-called Studio School established by Dorothy Dunn. Much to his father’s chagrin, Houser applied and was accepted.

“I was twenty years old when I finally decided that I really wanted to paint. I had learned a great deal about my tribal customs from my father and my mother, and the more I learned the more I wanted to put it down on canvas. That’s pretty much how it started.”

As a student at the Indian School from 1934-38, Houser came to believe that Dunn’s teachings were restrictive and unimaginative.The Indian School period is also when he changed his name from Haozous to Houser, having been “suggested” to do so by school administrators..

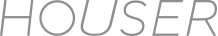

Despite the artistic restrictions imposed upon him by his teacher, he flourished. In 1937, Allan had his first solo exhibition (19 watercolor paintings) at the Museum of New Mexico. Within two years of graduating from the Indian School, he had already shown his work at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Golden Gate International Exposition, and the New York World’s Fair. In addition, he received a commission to paint full-size murals in the Department of the Interior’s Washington, D.C. headquarters. He briefly returned to Fort Sill to study with the Swedish muralist Olle Nordmark, who encouraged Houser to take up sculpting. Following Nordmark's suggestion, he completed his first wood carvings later that year. In the year 1939 Allan Capron Haozous and Anna Marie Gallegos were married.

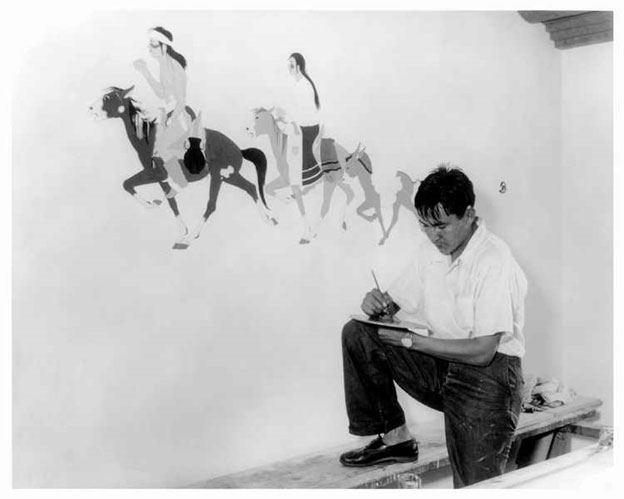

Despite the commission and exhibits, work was scarce after leaving the Indian School. Because of this scarcity and need to support his growing family, Houser relocated to Los Angeles in 1942, where he worked as a pipefitter’s assistant until 1947. Ever curious and indefatigably devoted to art, he continued to work on his art in the evenings. During this time period, Allan befriended students and faculty at the Pasadena Art Center, where he was exposed to the work of sculptors such as Jean Arp, Constantin Brâncuși, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, and Barbara Hepworth. This exposure laid the foundation for what would later become Allan Houser's own take on modernist sculpture.

In 1948, the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas awarded Allan Houser a commission that essentially launched his sculpting career. Comrade in Mourning, the carrara marble memorial he sculpted, remains one of his most iconic works. A year later, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. When the money from the fellowship ran out, he accepted a teaching position as artist-in-residence at Brigham, Utah’s Inter-Mountain School.

Houser taught at the Inter-Mountain School for 11 years, while also drawing, painting, and sculpting. “The first half of his career he was a painter,” recalled his son Phillip (in a 2014 newspaper interview). “I didn’t really notice what he was painting back then. It was just Dad doing what he did. But he liked to be on his own...without interruption. It wasn’t until later, when I saw a sculpture my father did of Geronimo, that I recognized what my dad was doing.”

Renowned as both an exceptional artist and educator by this time, Houser jumped at the chance to join the faculty of the newly created Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There, he set up the sculpture department and honed his status as one of America’s foremost, modernist sculptors. Within the studios at IAIA and the ones he built for himself, Houser chipped away at popular conceptions of what sculpture should be. In the process, he transformed Native American art from the parochial to the monumental.

In 1975 (age 61), Houser retired from teaching to focus exclusively on his art. Not only a genius visual artist, he was also a talented musician, who played several instruments well.

The post-retirement period was probably his most prolific: it allowed time for exploration and innovation.. During this period, Allan Houser-Haozous dedicated art works to the United Nations, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Smithsonian Institution. In 1992, he became the first Native American awarded the National Medal of Arts. In 1994, he passed away. Throughout his widely acclaimed career, Allan Houser-Haozous continually challenged himself. He became a leader in the evolution and definition of contemporary art. Houser's work continues to influence that of both Native and non-Native, modern artists.